Groundswell Network Boost: Testimony Project in collaboration with New Sanctuary Coalition in New York City seeks to document immigrant stories

By Jonathan Earle, Janice Amaya, and Maggie Von Vogt

In recent conversations between Groundswell Core Working Group members regarding government repression of immigrants and refugees, we encountered shared feelings of sadness, anger, and powerlessness. All of us agreed that we want to continue to explore and promote the important role that oral history can play to humanize, contextualize, and understand the root causes of migration and humanitarian crises.

We know there are so many oral historians, story tellers, organizers, activists, journalists, and leaders working to amplify the voices of immigrants and refugees and fortify the very movements that defend our immigrant and refugee communities. To this end, we are putting together a series of written profiles to highlight initiatives using oral history in collaboration with immigrant and refugee rights organizing in and outside of the United States. Our first profile in this series highlights the work being done by a team of folks in the New Sanctuary movement. Read our interview below with Jonathan Earle and Janice Amaya of the Testimony Project, a group documenting immigrant stories in collaboration with the New Sanctuary Coalition (NSC) in New York City.

Stay tuned for more of these interviews, as well as a series of Practitioner Support Network online sessions specifically designed around oral history and immigrant and refugee rights.

1. What is your project? If it has a name, what is it called (and why)? It doesn’t have an official name but we call it the “Testimony Project,” since bearing witness is central to what we do. Our friends’ survival has so often depended on them being invisible. We hope that by recording and sharing their stories, we can fight their dehumanization.

Here are two examples of interviews we've conducted:

2. How did your project come about? The idea of doing a podcast was kicking around the New Sanctuary Coalition (NSC) since at least last Fall. Among the more experienced volunteers, who hear so many stories, there was a sense that, “Somebody needs to record this.” Or to put it another way, “If everybody could hear this, things would have to change.” Throughout the Fall we discussed ideas for a storytelling project, but nothing stuck. And then in January, two NSC leaders were detained by ICE in quick succession. Co-founder Jean Montrevil was deported to Haiti, and executive director Ravi Ragbir was sent to a detention facility in Florida. At that point we knew it was time to stop trying to develop the perfect storytelling project and start recording. We were especially fortunate to find each other because we’re all in the business of storytelling: Jon is a podcaster, Ben does sound design, and Janice is in the theater.

3. Which organizations or social movements does your oral history project connect with? How does the organization/movement use the oral history project to support their work? We’re a part of the New Sanctuary Coalition, an interfaith group in New York City that defends immigrants at risk of deportation and supports their loved ones. Our storytelling project is aimed at fostering a community of resistance, spreading useful information, and comforting those in need. New Sanctuary helps us identify potential storytellers and shares interview clips on social media. We’ve recently begun connecting with other organizations (including Groundswell!). We wrote a blog post for Voice of Witness, which publishes oral history books with a social justice angle. And we’re in the early stages of a project to develop documentary theater pieces based on the oral histories. Overall, we’re excited to work with activists and artists to bring these stories to the public in creative ways.

New Sanctuary Coalition Executive Director Ravi Ragbir shortly after his release from ICE.

4. How is (or was) your oral history project organized? How are interviews set up? What does the process look like? New Sanctuary staff members nominate interviewees who are in a place—emotionally and with regard to their immigration case—where they might be comfortable talking. We explain the project, receive consent to record, and then let the narrator steer the conversation. Sometimes we ask questions based on what’s shared; sometimes we just listen. The most important thing is that the narrator feels seen and heard, and has an opportunity to speak to what they’ve rarely, if ever, had a chance to air.

5. What kinds of challenges have you encountered in this process? A challenge that is felt by a lot of people desperate to help: how do I ensure this causes no harm? We think about “do no harm” constantly and do our best to abide by it. We approach storytellers who we feel are ready to share their story. If a potential interviewee is in a state of emergency, or if they’re tired of telling their story, we don’t record. Our narrators decide what to talk about, in how much detail, and with what level of anonymity. And finally, when sharing stories outside New Sanctuary, we always err on the side of privacy. We’ve consulted with an immigration lawyer on basic guidelines for protecting our friends’ privacy.

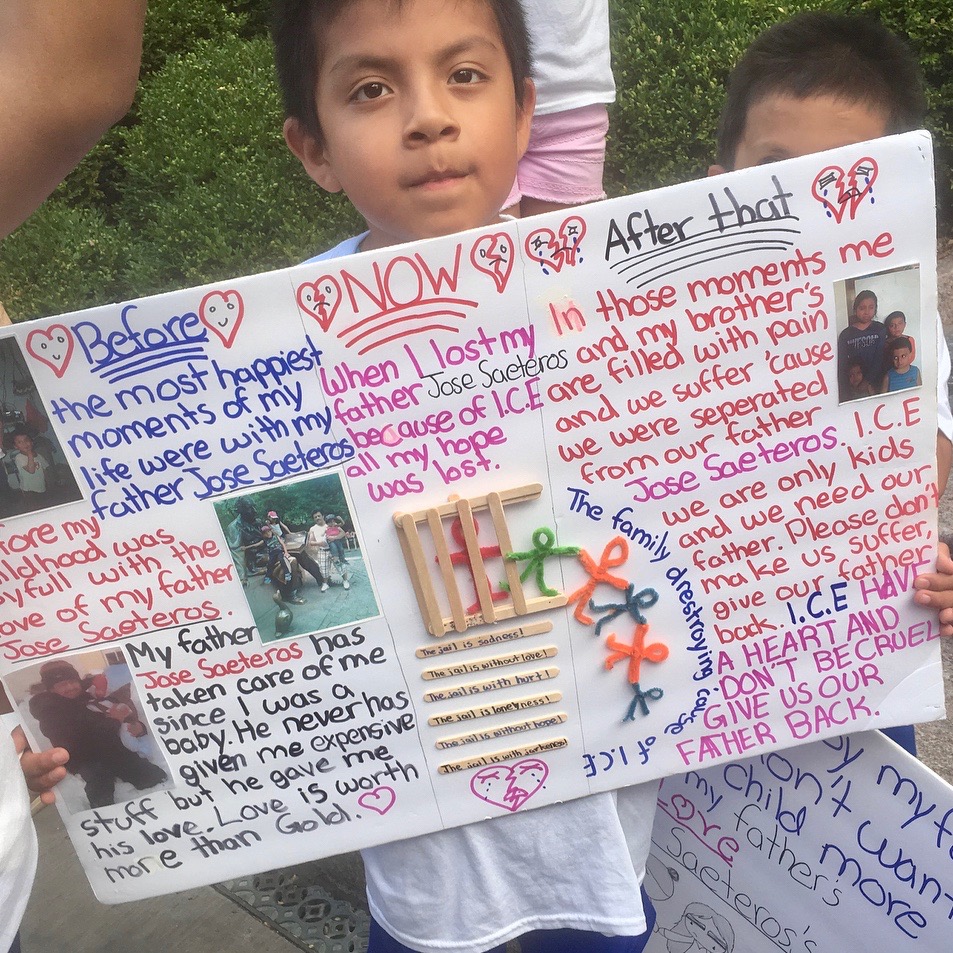

Young activists at an anti-deportation rally in May 2018. Photo by Jon Earle.

6. What issues have you encountered in ensuring the security and well being of the folks interviewed in your project, or what mechanisms have you put in place for security and caring for people talking about painful or traumatic experiences? Our practice is informed by trauma and oral history training. We make sure narrators understand the interview process, our plans for the recordings, and know that they can stop at any time. We use open-ended questions and silence when appropriate, since some storytellers want us to ask questions. Tissues, water, a shoulder, a laugh—they’re all ready. It helps that we’re part of a community where it’s OK to be at-risk and undocumented, so when narrators speak with us, they know they’re talking to members of their community. We’re supporters first, interviewers second. We accompany them to ICE check-ins and court hearings. We contribute to New Sanctuary’s bond fund. We attend rallies. We write letters on their behalf. We’re there. And because we’re there, if we hear something that raises concerns about a person’s safety, we can raise those concerns with somebody in the organization who is in a position to help.

A young activist at a July 2018 rally. Photo courtesy of the New Sanctuary Coalition.

7. What kinds of exciting and wonderful things have you encountered in this process? We’ve spoken with some truly remarkable people—people who’ve gone through unimaginable hardship and somehow emerged kinder and stronger; people who’ve chosen hope when despair was justified. They’re a testament to resilience and the power of community. In addition to painful stories about border crossings, detentions, and family separations, we’ve also recorded so much joy: A couple meets in the subway and falls madly in love. A father is reunited with his son after four months in detention. We’ve observed that pain and love are sides of the same coin, since painful stories are often an opportunity to talk about a person they love. And then there are the everyday moments. One woman told us about encountering Palmolive dish soap, the green kind, for the first time in America. "They make this fancy soap to wash dishes!? I couldn't stop smelling it!" she exclaimed. These are a sheer delight to record.

8. In your opinion and based on this experience, what does oral history offer to the issues of immigrant justice and refugee rights? Oral history is a powerful tool for rehumanizing undocumented immigrants, whom the president paints as dangerous criminals, exploiting widespread ignorance and fear. The truth is that immigrants are our parents, siblings, neighbors, and friends. They are us. The stories we’ve gathered also demonstrate that our immigration laws are indefensible. Any law used to deport good people, tear families apart, and destroy lives is immoral and unworthy of respect. Ultimately we hope that our work sends a single galvanizing message: immigrant lives matter.

9. What can the Groundswell: Oral History for Social Change network do to support your project? We’re hoping that the network can help us connect with mentors, collaborators, and other practitioners who can help us develop this project further.

10. Anything else you'd like to add? Love and solidarity ✌️

Janice Amaya is a Salvadoran-American theater artist and activist. She is a founding member of The Hummm, a theater collective whose aim is to democratize the experimental. While in graduate school, she began recording people's stories near the southern border of Mexico, her home state of Texas, and up to New York City where she now resides. She holds an MFA from the Moscow Art Theater and Harvard University.

Jon Earle is a Brooklyn-based documentarian and Russian translator. His audio work has aired on KCRW and NHPR, and appeared on the Spotify podcast United States of Music. He produces Success @ Sinai, a podcast for the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Jon is an alumnus of the Transom Story Workshop and the Oral History Summer School.

Maggie Von Vogt is Groundswell's Operations Coordinator. She is a community-based educator, organizer, and media maker focusing on issues in Central America, immigration, and the environment. She lives in Northern California.

If you or anyone you know is also doing oral history work to support immigrant and refugee rights, contact us at the following email addresses: maggie@oralhistoryforsocialjustice.org and fanny@oralhistoryforsocialchange.org.